Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) published more than 30 books, and it was her best-selling anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin that catapulted her to international celebrity and secured her place in history. She believed her actions could make a positive difference.

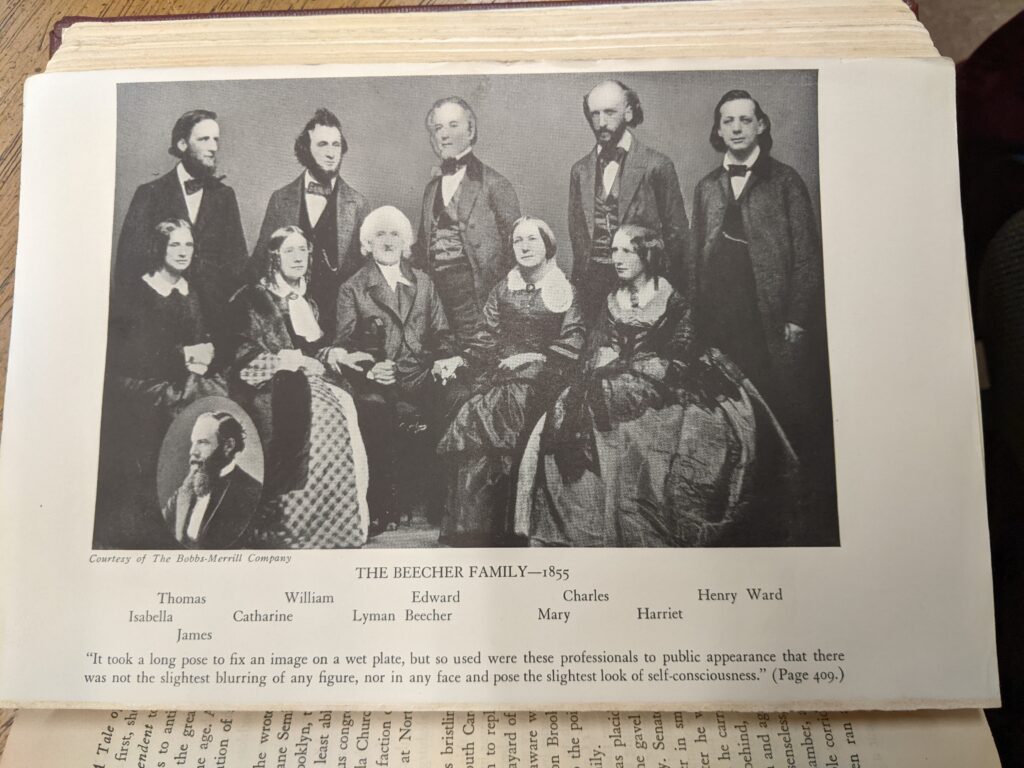

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher was born June 14, 1811 in Litchfield, Connecticut, to the Rev. Lyman Beecher (1775-1863) and Roxanna Foote Beecher (1775-1816), the sixth of eleven children.

The Beechers expected their children to shape the world around them:

- All seven sons became ministers, then the most effective way to influence society

- Oldest daughter Catharine pioneered education for women

- Youngest daughter Isabella was a founder of the National Women’s Suffrage Association

- Harriet believed her purpose in life was to write. Her most famous work exposed the truth about the greatest social injustice of her day, human slavery

When Harriet was five years old, her mother died and her oldest sister Catharine assumed much of the responsibility for raising her younger siblings. Harriet showed early literary promise: At seven, she won a school essay contest, earning praise from her father. Harriet’s later pursuit of painting and drawing honored her mother’s talents.

Lyman’s second wife, Harriet Porter Beecher (1800-1835), added her own children, Isabella, Thomas and James, to the eight already in the household.

In Litchfield, and on frequent visits to her grandmother in Guilford, CT, Harriet and her siblings played, read, hiked, and joined their father in games and exercises. Many of these childhood events were incorporated into Harriet’s last novel Poganuc People (1878).

As a young girl, Harriet took part in lively debates at the family table. By discussing current events and social issues, Harriet learned how to argue persuasively.

She began her formal education at Sarah Pierce’s academy, one of the earliest institutions to encourage girls to study academic subjects in addition to the traditional ornamental arts.

In 1824, Harriet became first a student and then a teacher at Hartford Female Seminary, founded by sister Catharine. There, she furthered her writing talents, spending many hours composing essays.

In 1832, 21-year-old Harriet Beecher moved with her family to Cincinnati, Ohio, when her father Lyman was appointed President of Lane Theological Seminary. There she met and married Calvin Stowe, a theology professor she described as “rich in Greek & Hebrew, Latin & Arabic, & alas! rich in nothing else…”

Six of Stowe’s seven children were born in Cincinnati. In the summer of 1849, Stowe experienced for the first time the sorrow of many 19th century parents when her 18-month-old son, Samuel Charles Stowe, died of cholera. Stowe later credited that crushing pain as one of the inspirations for Uncle Tom’s Cabin because it helped her understand the pain enslaved mothers felt when their children were sold away from them.

In 1850 Calvin Stowe joined the faculty of his alma mater, Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine. The Stowe family moved and lived in Brunswick until 1853.

After the Civil War, the Stowes purchased a house and property in Mandarin, Florida, on the St. John’s River and began to travel south each winter. The relatively mild winters of northern Florida were a welcome respite from Hartford’s cold and the high costs of winter fuel.

The Beechers and the Stowes knew that racial equality required more than legislation; it also required education. Stowe’s brother Charles Beecher (1815-1900) opened a Florida school to teach emancipated people and he had urged Calvin and Harriet Stowe to join him.

Newly expanded railroads made shipping citrus fruits north a potentially lucrative business. Stowe purchased an orange grove which she hoped her son Frederick would manage.

Harriet Beecher Stowe loved Florida, comparing its soft climate to Italy, and she published Palmetto Leaves (1873), describing the beauties and advantages of the state. Stowe and her family wintered in Mandarin for more than 15 years before Calvin’s health prohibited long travel.

Stowe was less than half way through her life when she published Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She continued to write and work to improve society for most of her days. From Brunswick, the Stowes moved to Andover, Massachusetts, where Calvin was a professor of theology at Andover Theological Seminary (1853-1864).

After his retirement, the family moved to Hartford, Connecticut. There, Harriet Beecher Stowe built her dream house, Oakholm, in Nook Farm, a neighborhood full of friends and relatives. The high maintenance cost and encroaching factories led her to sell her mansion in 1870. In 1873, Harriet, along with her husband and two adult daughters, settled into a brick Victorian Gothic cottage on Forest Street where she remained for 23 years.

While living in Hartford, Stowe undertook two speaking tours, one along the east coast, the second taking her to the western states. Promoting progressive ideals, she worked to reinvigorate the art museum at the Wadsworth Atheneum and establish the Hartford Art School, later part of the University of Hartford.

Stowe wrote some of her best known works, after Uncle Tom’s Cabin, while living in Hartford: The American Woman’s Home (1869), Lady Byron Vindicated (1871) and Poganuc People (1878).

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s writing career spanned 51 years. She published 30 books and countless short stories, poems, articles, and hymns. She learned early that her writing contributed to the family income. With her writing, Stowe could publicly express her thoughts and beliefs in a time when women were discouraged from public speaking, and could not vote or hold office.

Stowe’s publishing career began with:

- Primary Geography for Children (1833)

Her sympathetic approach to Catholicism, unusual for its time, won her the praise of the local bishop. - New England Sketches (1835)

A short story collection.

These were followed by:

- The Mayflower: Sketches of Scenes and Characters among the Descendants of the Pilgrim (1843)

- The Coral Ring (1843)

A short story which promoted temperance and an anti-slavery tract. - Numerous articles, essays and short stories published regularly in newspapers and journals

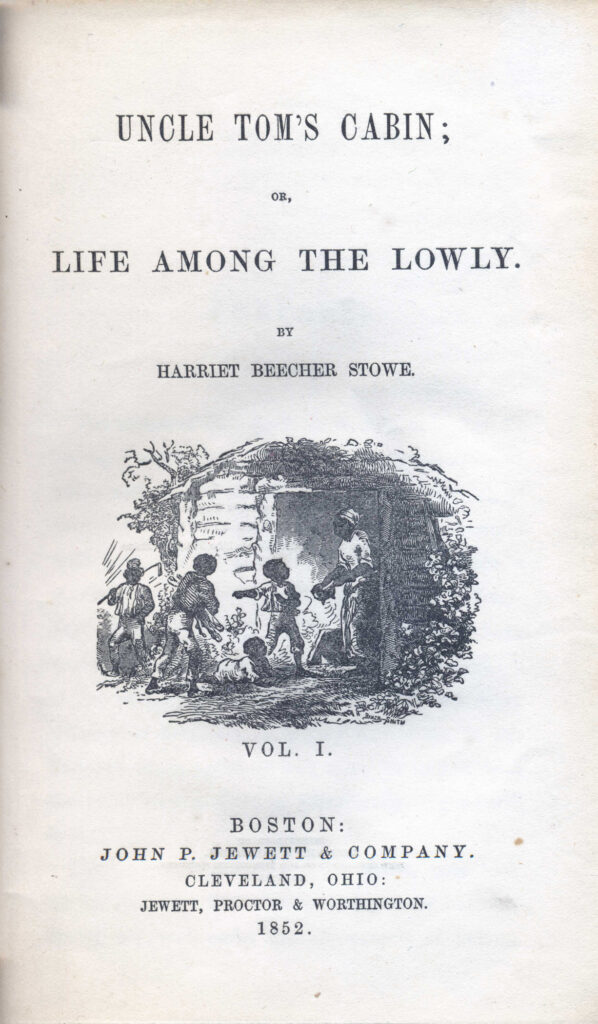

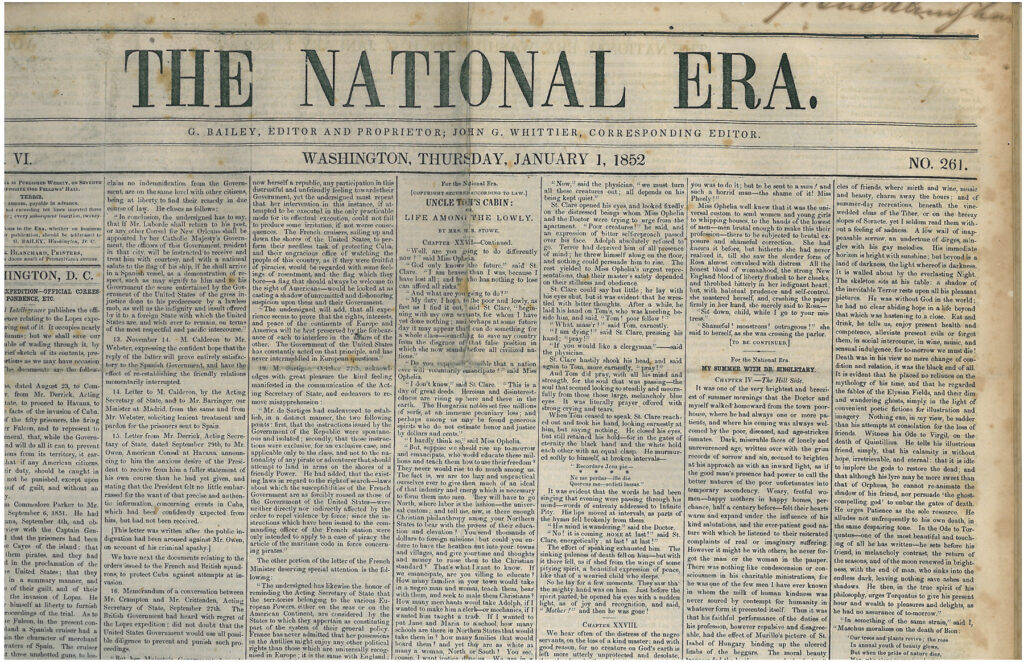

In 1851, The National Era publisher Gamaliel Bailey contracted with Stowe for a story that would “paint a word picture of slavery” and that would run in installments in the abolitionist newspaper. Stowe expected Uncle Tom’s Cabin or Life Among the Lowly to be three or four chapters. She wrote more than 40.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin brought Stowe financial security and allowed her to write full time. She published multiple works each year including three other antislavery works: The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853) documenting the case histories on which she had based Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Dred: A Tale of the Great Dismal Swamp (1856), a forceful anti-slavery novel, and The Minister’s Wooing (1859) encouraging a more forgiving form of Christianity.

- The American Woman’s Home

A practical guide to homemaking, co-authored with sister Catharine Beecher - Lady Byron Vindicated

Which strove to defend Stowe’s friend lady Byron while immersing Stowe herself in scandal.

A comprehensive bibliography for Harriet Beecher Stowe can be found at the University of Pennsylvania website.

Harriet Beecher Stowe née Harriet Elisabeth Beecher, was born June 14, 1811, in Litchfield, CT to the Rev. Lyman Beecher (1775-1863) and Roxana Foote Beecher (1775- 1816), the seventh of Lyman’s thirteen children; though only eleven lived to adulthood. The Beechers were one of the most influential families of the 19th century.

Roxana Foote (1775-1816), was Lyman Beecher’s first wife and Harriet’s mother. She and Lyman married in 1899; Roxana was a granddaughter of Revolutionary General Andrew Ward, was literate, artistic, and read mathematical and scientific treatises for pleasure. She had nine children.

Lyman Beecher was among the best-known clergymen of the first half of the 1800s. He began attracting national attention in the 1820s when he preached anti-slavery sermons in response to the Missouri Compromise. Lyman’s conservative beliefs, charisma and dynamic preaching affected all his children. He taught them that a personal commitment was necessary for their spiritual salvation, but he also taught them to think for themselves and to ask questions. The Beecher children grew into adults who shared their father’s love of God, yet they came to describe God in more loving and forgiving terms. Like their father, though, the Beechers believed the best way of serving was action to make a better world.

Lyman Beecher’s second wife, Harriet Porter Beecher (1790-1835), whom he married in 1817, had four children. Lyman married his third wife, Lydia Beals (1789-1869) in 1835; they had no children, but Lydia, a widow, had five children from her previous marriage.

Lyman Beecher’s Children and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s siblings:

- Catharine Esther Beecher (1800-1878)

- William Henry Beecher (1802 – 1889)

- Edward Beecher (1803 – 1895)

- Mary Foote Beecher Perkins (1805-1900)

- Harriet (1808-1808)

- George Beecher (1809-1843)

- Harriet Elisabeth Beecher (1811-1896)

- Henry Ward Beecher (1813-1887)

- Charles Beecher (1815 –1900)

- Frederick (1818-1820)

- Isabella Holmes Beecher Hooker (1822-1907)

- Thomas Kinnicut Beecher (1824-1900)

- James Chaplin Beecher (1828-1886)

Founder of multiple schools including the Hartford Female Seminary, Catherine Beecher was a prolific writer who co-authored The American Woman’s Home (1869) with her sister Harriet.

Catharine Beecher was the eldest Beecher child. She attended Miss Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy, one of the best schools of its time for girls and young women. When Catharine’s mother Roxana Foote Beecher died in 1816, Catherine became responsible for her siblings.

In 1824, with the help of her brother Edward and sister Mary, Catharine opened the Hartford Female Seminary on Main Street in Hartford, CT. At first, Catharine and Mary were the only teachers. Harriet joined the staff in 1827 following the completion of her own education at the Seminary. Catharine found many of the textbooks unsatisfactory and decided to write her own. Students learned rhetoric, logic, natural and moral philosophy, chemistry, history, Latin, algebra and drawing.

Most 19th century girls expected to marry and manage homes, and parents felt their daughters needed little formal education. Catharine argued that running a home was as complicated as running a business, and that young women should be instructed in these responsibilities the same way boys received instruction for their careers. Catharine Beecher prepared young women for the future, training them to become teachers.

When Lyman Beecher became the president of Lane Seminary in Cincinnati, OH in 1832, Catharine found a successor to run the Hartford Female Seminary and moved west with him. In Cincinnati she founded the Western Female Institute, and went on to establish schools in Iowa, Illinois and Wisconsin.

Catharine Beecher was a prolific writer on topics ranging from education and religion to health and home economics. Her best known work was A Treatise on Domestic Economy (1841). In 1869, she co-authored The American Woman’s Home with her sister Harriet.

A preacher with parishes from Rhode Island to Connecticut, Ohio, New York and Massachusetts, William Henry Beecher was an advocate of abolition and temperance.

William Henry Beecher was Lyman and Roxana’s oldest son. Less scholarly but more mechanically skilled than his siblings, William apprenticed as a cabinetmaker and clerk in Hartford and New Milford CT, and New York City before becoming a licensed preacher in 1830. His first parish was in Newport, RI. Over the next 20 years William worked at churches in Middletown, CT, Putnam, OH, Batavia, NY, Euclid, OH, and finally North Brookfield, MA, where he remained for nearly two decades. He was an advocate of Spiritualism and phrenology, publishing an article in Fowler’s Phrenological Journal.

He wed Katherine Edes of Massachusetts in 1830, and they had six children. Katherine shared William’s commitment to anti-slavery and temperance. When she died in 1870, he retired and moved to Chicago to live with his daughters. One of the least famous Beechers, William was an early advocate of abolition, and promoted temperance as a means to broader social reform.

An abolitionist advocate, Edward Beecher believed that all of America was responsible for slavery since the entire society profited from it.

Edward Beecher entered Yale at 15, and worked his way through college by teaching, graduating as class valedictorian. More religiously liberal than his father, he blended Lyman Beecher’s old Calvinism with the newer tenets of Unitarianism, and explored Spiritualism. Edward was also more liberal on social reform. He embraced abolitionism, or the immediate end to slavery, as opposed to Lyman Beecher’s support of colonization. Edward was friends with abolitionist Rev. Elijah Lovejoy and left him just hours before Lovejoy was killed by a mob in 1837. In response, Edward published a Narrative of the Riots at Alton, an indictment of slavery and mob violence. Edward believed that all of America was responsible for slavery, since the entire society profited from it. His writing helped fuel the fire that would lead to younger siblings Harriet’s and Henry’s fame. The earliest known letter written by young Harriet Beecher was to her brother Edward in 1822 as he studied at Yale.

Edward’s wife, Isabella Porter Jones, wrote Harriet Beecher Stowe “If I could use a pen like you, Hatty, I would write something that would show the entire world what an accursed thing slavery is.” Edward and Isabella had 12 children, including one with special needs whom the Beechers incorporated into family life – an exception to 19th century practice.

Mary was the only Beecher sibling who elected not to pursue a public life.

Mary was the only daughter of Lyman Beecher’s who did not pursue public life, though she had a central role in the extended Beecher family. Mary received her primary education at Miss Pierce’s school in Litchfield, CT with her sisters Harriet and Catherine. She partnered with Catharine Beecher to open the Hartford Female Seminary, but disliked teaching. She married Thomas C. Perkins, a prominent lawyer in Hartford, and settled there for the rest of her life. She and Thomas had four children. She is the grandmother of author Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

Harriet died in infancy. Harriet Elisabeth was named in her memorial.

A minister and abolitionist, George Beecher held a strong interest in Perfectionism.

George Beecher, the fifth of Lyman Beecher’s children, attended Miss Porter’s Academy with his siblings and went off to Hartford Grammar School when he was 14. At 16, George enrolled at Yale College to study the ministry. He left Yale to go with Lyman and the family to Ohio in 1832. There he was ordained as a minister and accepted his first pastorate in Batavia, OH. George married Sarah Buckingham of Batavia in 1839, and they had a son. Like his older brother Edward, George was an abolitionist, and joined the Anti-Slavery Society.

Batavia, like many small churches, had difficulties paying their minister, and George relocated to Rochester, NY. Rochester was at the heart of the Burned Over district of western New York, so-named because of the repeated religious revivals and reform movements that swept through the area. As a Beecher raised to improve both himself and society, George found many new ideas here. He was particularly attracted to Perfectionism.

George and Sarah Beecher returned to Ohio, where George began writing about Perfectionism, teaching music, and studying plants. In July of 1843, he walked into his gardens to shoot some birds and was found dead of a gunshot wound. The Beechers believed that it was an accidental death and the family mourned their brother. Harriet Beecher Stowe confessed that “the sudden death of George shook my whole soul like an earthquake.”

One of the most famous U.S. men in of his time, Henry Ward Beecher shaped Brooklyn’s Plymouth Church into one of the most influential pulpits of the 19th century.

Henry Ward Beecher, the seventh child of Lyman Beecher and Roxana Foote Beecher, became one of the most famous men in the United States during the 19th century. Among the Beecher family, only sister Harriet bested Henry’s lifetime celebrity and historical legacy.

Henry was only three when his mother Roxana died. The toddler formed a close reliance on five-year-old Harriet, and their bond remained throughout their lives. As a boy, Henry was more attracted to open pastures and wooded fields than schools or books. As an adult, Henry turned this early affinity for nature into visions of a loving deity.

Henry was barely 13 when his father Lyman and step-mother Harriet Porter Beecher moved from Litchfield, CT to Boston, MA. The city held only one attraction for Henry – sailing ships. Henry Ward Beecher, like many 19th century children, associated ships and the sea with adventure and freedom from the structure of schooling.

Lyman Beecher convinced him to study at Mount Pleasant Institute in Amherst, MA. Henry found Mount Pleasant’s military-type discipline difficult, but the school gave him the skills to become a powerful orator. By the time Henry graduated, the boy who had been embarrassed into silence by a childhood speech impediment presented speeches and performed in plays. This talent, coupled with a religious renewal, led to Henry’s determination to become a minister and admission to Amherst College in 1830. While at Amherst, Henry met Eunice White Bullard, the sister of a schoolmate and daughter of a physician. The two became engaged to marry, but it would be years before they wed.

After graduating from Amherst College in 1832, Henry joined his family in Cincinnati, OH and enrolled in Lane Seminary. After completing his studies, Henry married Eunice in 1837 and the newlyweds moved to Lawrenceburg then Indianapolis, IN. Henry and Eunice ultimately had 11 children, but only four lived to maturity. Neither parish could afford to pay well, and the young family struggled. In 1847, Henry and Eunice’s poverty ended when Henry was recruited by Henry C. Bowen, a wealthy merchant, newspaper editor, and anti-slavery advocate in Brooklyn, NY. Henry shaped Plymouth Church into one of the most influential pulpits in the United States. By 1850 the crowds coming to hear Beecher’s sermons on temperance and the wrongs of slavery could not fit inside the building.

Henry Ward Beecher actively used Plymouth Church to fight slavery. Staging elaborate mock auctions, Henry led his congregation to redeem enslaved individuals by purchasing their liberty. Following repeal of the Missouri Compromise and the passage of the Kansas Nebraska Act, Plymouth Church paid to ship rifles to anti-slavery settlers in Kansas and Nebraska in crates marked “Bibles.” These rifles became known as “Beecher’s Bibles.”

President Abraham Lincoln sent Henry to London during the Civil War to persuade Great Britain to remain neutral. At the close of the Civil War, Beecher was given the symbolic prize of presenting a sermon at Fort Sumter when the U.S. flag was once again raised there.

In 1872, Victoria Woodhull, a controversial woman’s rights advocate, accused Henry of committing adultery with Elizabeth Tilton, wife of Theodore Tilton. The Tiltons were members of Plymouth Church, and Theodore was co-editor with Henry of The Independent, and a close friend. In 1875, Theodore Tilton sued his former friend for “alienation of affection.” The resulting trial lasted more than six months and became the most notorious scandal of the 19th century.

Opinions over Henry’s guilt caused rifts in society, Plymouth Church, and the Beecher family itself. Sisters Harriet and Isabella were temporarily estranged. Harriet was her brother’s supporter and advocate while Isabella believed Victoria Woodhull. Ultimately a civil jury was unable to reach a conclusion, and a mistrial was declared. Henry continued to work at Plymouth Church, and despite the controversy, remained a popular figure. When he died of a stroke in 1887, Brooklyn held a day of mourning, the New York legislature adjourned its session, and national figures led the funeral procession.

A natural scholar with a love for music, Charles Beecher moved to New Orleans in 1838. His letters provided sister Harriet with first-hand accounts of slavery which she later incorporated in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Lyman and Roxana’s youngest child, Charles, spent his earliest years in Litchfield, but at 11 he moved to Boston with his father and stepmother. There he attended Boston Latin School and Lawrence Academy before entering Bowdoin College. In 1834 he joined his family in Cincinnati to continue his theological training at Lane Seminary.

Charles was a tall athletic man, a natural scholar and gifted in languages, but his first love was music. He played the violin and organ and tried to support himself as a musician, giving lessons, playing in churches, and writing articles on music theory.

In 1838, Charles moved to New Orleans and supplemented his income as a church organist by collecting fees for a counting house. His years in New Orleans, and the letters he wrote home, provided first-hand accounts of slavery that sister Harriet Beecher Stowe later incorporated in her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

In 1840 Charles married Sarah Coffin of Massachusetts. Charles and Sarah returned north in 1841 and joined his brother Henry Ward Beecher in Indianapolis where he ran the music program for Henry’s church, Henry’s sermons helped inspire Charles to become a minister. Charles brought his passion for music to his sermons and was immediately popular with the congregation. In 1844 he was installed as pastor of the Second Presbyterian church in Fort Wayne, IN. Charles also served as minister of churches in New Jersey and Massachusetts.

Some of Charles Beecher’s religious beliefs were controversial, and in 1863 while he was in Georgetown, MA, he was tried for heresy. When Charles was found guilty, his Georgetown church split between his supporters and his critics. Charles was asked to remain at the First Congregational Church and was subsequently elected to the Massachusetts General Assembly for 1864. The heresy conviction was later overturned.

Charles kept a journal when he accompanied his famous sister Harriet on her first trip to Great Britain and Europe in 1853. Harriet published Sunny Memories of Foreign Lands in 1854, crediting her brother for his keen observations. Charles was a successful author and his publications included works on the Fugitive Slave Act, theology, Spiritualism, and the autobiography and correspondence of his father, Lyman Beecher. Charles continued to write and publish until late in life.

The 1860s were difficult for Charles and his wife Sarah. In addition to his heresy conviction, their son Frederick was badly wounded at Gettysburg that same summer, two of their daughters, Hattie and Essie drowned in 1867, and Frederick, who had recovered from his war injuries and remained in the army, was killed in 1868 in a battle with the Cheyenne in what is now Colorado.

Weary of the duties of a small town pastor, Charles and Sarah moved to Newport, FL in 1870 where Charles served as Florida’s State Superintendent of Public Instruction for two years.

Frederick, Harriet Porter’s first child, died of scarlet fever.

Isabella was the first child of Lyman Beecher and his second wife, Harriet Porter Beecher. Isabella began her education at Catharine Beecher’s Hartford Female Seminary and lived with her sister Mary Perkins. In 1841 she married John Hooker, a descendant of Thomas Hooker, the founder of Hartford. John Hooker was a lawyer and an abolitionist.

In the early 1860s Isabella got involved in the woman’s suffrage movement. Isabella joined Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony as a member of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association in 1869. She was a founding member of the Connecticut Woman’s Suffrage Association. Isabella’s ideas of equality were influenced by John Stuart Mills’ On Liberty and the Subjection of Women.

In 1871, Isabella organized the annual convention of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association in Washington D.C. and presented her argument before the Committee on the Judiciary of the United States Senate. Her husband, John Hooker, believed in his wife and supported her activities. He helped Isabella draft a bill to the Connecticut Legislature giving married women the same property rights as their husbands. The bill passed in 1877. Isabella annually submitted a bill granting women the right to vote, but it did not pass in her lifetime.

A political and social conservative, unlike most of his siblings, Thomas Kinnicut Beecher was an educator and minister.

From a young age, Thomas Beecher had shown a disinterest in the ministry and an aptitude for natural sciences and education. He graduated from Illinois College, and helped his older brother Henry in his Indiana church for a short time. Like Catharine Beecher, he turned to education as a career. He taught in Philadelphia, and spent two years at Hartford Public High School. In 1850 he married Hartford native Olivia Day, who died in childbirth in 1853. By then Thomas had followed his older brothers and accepted a position at New England Church in Williamsburg, NY.

Thomas also differed from most of his Beecher siblings in being more politically and socially conservative. Up to the beginning of the Civil War he opposed abolition as too radical. He disagreed with the woman’s rights movement that his sister Isabella and brother Henry supported. These views led to his dismissal, and he accepted a call from the Independent Congregational Church in Elmira, NY in 1853. Among his parishioners were the Langdon family, whose daughter Olivia would marry Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain). Thomas officiated at their wedding at his church, joined by Twain’s friend, Joseph Twitchell. Thomas himself remarried in 1857. His second wife, Julia Jones, was his first wife’s cousin. Julia and Thomas adopted three daughters.

Despite Thomas’ anti-abolition stance there is evidence he participated in the Underground Railroad. He joined the Union army, serving as a chaplain in the 141st New York Volunteers, the same regiment where his brother James was an officer. He disagreed with the expansion of legal rights for women, yet acknowledged his wife’s crucial role in running his parish, and accepted a woman as his own minister after he retired. He was a temperance advocate who showed remarkable compassion to his sister-in-law Anne Beecher’s alcoholism.

Thomas died of a stroke in 1900. He is buried in Elmira, NY.

After serving as a ship’s officer in the East India trade, James Chaplin Beecher became a minister, eventually taking over brother Henry’s Plymouth Church.

James C. Beecher was the youngest child of Lyman and Harriet Porter Beecher. Like his half-sister Harriet, James lost his mother while he was very young. He was raised by Lyman Beecher’s third wife, Lydia Beecher. Less scholarly than his older brothers, James eventually graduated from Dartmouth, then pursued a life at sea. He served on a coaster trading along the eastern U.S. coast, before sailing on a clipper ship for Canton, China. James served five years as a ship’s officer in the East India trade.

James returned from sea and entered Andover Theological Seminary, saying “Oh I shall be a minister. That’s my fate. Father will pray me into it!” While attending Andover he married Anne Morse, a widow with a young child. The couple had no other children. James and Anne left Andover to become missionaries in Canton and Hong Kong. In 1859, Anne Beecher returned from China for what the family euphemistically called health reasons. She appears to have suffered from drug and alcohol addiction. She spent time in sanitariums, and the water cure facility in Elmira, NY, near her brother-in-law Thomas Beecher.

James remained in China until the onset of the Civil War in 1861. He enlisted in the army and served as chaplain of the First Long Island Regiment, then as a lieutenant colonel in the 141st New York Volunteers. He briefly returned to civilian life because of concern over his wife Anne. After her death in 1863, he rejoined the army and was appointed to recruit an African American regiment, the First North Carolina Volunteers. That same year Harriet Beecher Stowe designed the regiment’s banner. The regiment later became the 35th United States Colored Troops and fought at the Battle of Olustee, Florida and Honey Hill, South Carolina.

After the Civil War, James was as pastor at Thomas Beecher’s church in Elmira, NY for nine months. In 1864 he married Frances “Frankie” Johnson, of Guilford, CT. The two opened a school in Jacksonville, FL for newly emancipated people. James and Frankie were married for 21 years and adopted three daughters. In 1867 he became pastor of the Congregational Church in Owego, NY, and later moved to Poughkeepsie. James purchased land in Ulster County to build a home for his family and to preach to the farmers of upstate New York.

In 1881 Henry Ward Beecher asked James to take over Plymouth Church. James reluctantly agreed, as he preferred a more rural life. He soon suffered what may have been a nervous breakdown and eventually went to Dr. Gleason’s water cure sanitarium in Elmira, NY, where his first wife had sought help. While in Elmira, James took his own life.

Harriet Beecher married Calvin E. Stowe (1802-1886) in 1836 in Cincinnati. Calvin was a respected scholar and theologian who taught at Lane Seminary in Cincinnati and later at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, ME, and Andover Theological Seminary in Andover, MA. Calvin’s Origin and History of the Books of the Bible was published in 1867. He encouraged his wife’s writing career, telling her she “must be a literary woman.”

Harriet Beecher Stowe and Calvin Stowe had seven children. Only three survived them.

Twins Hattie and Eliza were the oldest Stowe children. Lively Hattie was often her mother’s travel companion; the more reserved Eliza preferred to remain at home. Both daughters were well read and enjoyed political and intellectual discussion. Neither married; they lived with their parents, serving as correspondents and assistants for their mother, managing the family households and later taking care of their aging parents. After their parents died, the sisters moved to Simsbury, CT near their brother Charles.

Stowe called Henry “the lamb of my flock.” At 18, Henry traveled to Britain and Europe with his mother and family. Henry died at 19, in a swimming accident near Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H. Stowe’ grief at his death caused a crisis of faith and spurred her to write The Minister’s Wooing.

Frederick was “a smart bright lively boy – full of all manner

of fun & mischief, fond of reading more than of hard study,” according to his mother.

Fred attended Phillips Andover Academy in Andover, MA and Harvard Medical School. He left school to enlist in the army for the Civil War. Fred was wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg (1863), but re-enlisted and fought through 1864.

He and his family struggled unsuccessfully with his alcohol addiction. Fred went to California in 1870 and disappeared. Historians believe he died shortly after his arrival.

Fred was the inspiration for the character Tom Bolton in Stowe’s My Wife and I and We and Our Neighbors. Stowe insightfully describes alcoholism as an illness, at a time when most people believed it was a moral failure.

The Stowe’s youngest daughter Georgie was mischievous, lively, and artistic.

In 1865, she married the Rev. Henry Freeman Allen, an Episcopal priest. The couple’s only child, Freeman, was the Stowes’ first grandchild. Harriet and Calvin relished their roles as grandparents and often visited the Allens in Stockbridge, Amherst, and later Boston, MA. As an adult, Dr. Freeman Allen served as an army surgeon in the Spanish-American War and later specialized in anesthesia at Massachusetts General Hospital.

As an adult, Georgie became addicted to morphine first given to her as a painkiller after the birth of her son. She died of septicemia in Boston at age 47.

Harriet called her toddler Charley, “my sunshine child.” Charley died when he was 18 months during a Cincinnati cholera epidemic. Stowe was devastated. She said later her grief helped her empathize with enslaved families separated at the auction block. Her grief at Charley’s death fueled her descriptions of children and families in Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

The Stowes’ youngest son was rambunctious and gave his parents trouble. He ran away from school at 13 to become a sailor, but the Stowes found him before the ship set sail. His mother used his antics as a model for her story Our Charley.

Charles Stowe was ordained as a minister in 1878. He married Susan Monroe (1853-1918) and had three children. The young family lived at his parents’ Hartford home for a short time in 1883. From the mid 1880s until the late 1890s he was minister of the Simsbury, CT Congregational Church. Charles wrote a biography of his mother, The Life of Harriet Beecher Stowe, in 1889. Later editions were co-authored by his son Lyman.

Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-1896) published more than 30 books, but it was her best-selling anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin that catapulted her to international celebrity and secured her place in history. In 1851, Stowe offered the publisher of the abolitionist newspaper The National Era a piece that would “paint a word picture of slavery.” Stowe expected to write three or four installments, but Uncle Tom’s Cabin grew to more than 40.

In 1852, the serial was published as a two-volume book. Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a runaway best-seller, selling 10,000 copies in the United States in its first week; 300,000 in the first year; and in Great Britain, 1.5 million copies in one year. In the 19th century, the only book to outsell Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the Bible.

More than 160 years after its publication, Uncle Tom’s Cabin has been translated into more than 70 languages and is known throughout the world.

Since Connecticut was the last New England state to abolish slavery in 1848, Harriet could have been exposed to slavery as a child. Some of Harriet’s earliest memories were of two indentured African American women in her family household, and an African American woman employed by the family. As an adult, Harriet remembered how they comforted her after the loss of her mother.

As a young woman living in Ohio, Harriet traveled to neighboring Kentucky, a state where slavery was legal. There she visited a plantation which would serve as inspiration for the Shelby Plantation in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In Cincinnati, Harriet learned that even discussion of slavery could divide a community: most students at her father’s school, Lane Seminary, left in protest after anti-slavery debates and societies were forbidden.

Later, Stowe heard first-hand accounts from formerly enslaved people and employed at least one fugitive in her home. Her husband and brother helped shelter a man and helped along the informal underground railroad. And she was appalled by the stories of cruel separations of mothers and children. As a woman who had lost her mother and one of her own children, Stowe felt a kinship with these women.

As she began to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe enlisted friends and family to send her information and scoured freedom narratives and anti-slavery newspapers for first-hand accounts.

In the summer of 1849, Harriet’s 18-month-old son, Samuel Charles, died of cholera.

This crushing grief was incorporated into Uncle Tom’s Cabin; Stowe said it helped her understand the pain enslaved mothers felt when their children were sold away from them.

Then, on September 18, 1850, the U.S. Congress passed the Compromise of 1850. Among its provisions was creation of the Fugitive Slave Law. Although helping those who escaped slavery had been illegal since 1793, the new law required that everyone, including ordinary citizens, help catch alleged fugitives. Those who aided escapees or refused to assist slave-catchers could be fined up to $1,000 and jailed for six months.

After the law’s passage, anyone could be taken from the street, accused of being a fugitive from slavery, and taken before a federally appointed commissioner. The commissioner received $5 by ruling the suspected fugitive person was free, and $10 for ruling the person was “property” of an enslaver. The law clearly favored returning people to slavery. Free Black people and anti-slavery groups argued that the new law bribed commissioners to unjustly enslave kidnapped people.

Stowe was furious. She believed slavery was unjust and immoral, and bristled at an law requiring citizen — including her — complicity. Living in Brunswick, ME, while her husband taught at Bowdoin College, Stowe disobeyed the law by hiding John Andrew Jackson, who was traveling north from enslavement in South Carolina. When she shared her frustrations and feelings of powerlessness with her family, her sister-in-law Isabella Porter Beecher suggested she do more: “…if I could use a pen as you can, Hatty, I would write something that would make this whole nation feel what an accursed thing slavery is.”

For more than 200 years, slavery had been common practice in the U.S. Enslaved African-Americans helped build the economic foundations of the new nation and were a driving force in the growing economy. Following the American Revolution, the new U.S. Constitution had tacitly acknowledged slavery, counting each enslaved person as three-fifths of a person for the purposes of taxation and Congressional representation.

Abolitionist sentiment had provoked hostile responses north and south, including violent mobs, burning mailbags of abolitionist literature, and passage of a “gag rule” banning consideration of anti-slavery petitions in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Despite the threat of violent persecution, and her expected role as a respectable woman, Stowe put pen to paper, illustrating slavery’s effect on families and helping readers empathize with enslaved characters.

With the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, critics charged that Stowe had made it all up and that slavery was a humane system. Stowe followed with a nonfiction retort, The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853), compiling real-life evidence that had informed her novel.

Stowe’s words changed the world, yet the issues she wrote about persist; her work provokes us to think and act on issues facing our world today.

In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe shared ideas about the injustices of slavery, pushing back against dominant cultural beliefs about the physical and emotional capacities of black people. Stowe became a leading voice in the anti-slavery movement, and yet, her ideas about race were complicated. In letters to friends and family members, Stowe demonstrated that she did not believe in racial equality; she suggested, for example, that emancipated slaves should be sent to Africa, and she used derogatory language when describing black servants. Even in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe drew on popular and deeply offensive racial stereotypes when describing some of her characters. Though these beliefs seem to contradict Stowe’s commitment to anti-slavery, many white abolitionists believed that slavery was unjust while also believing that white people were intellectually, physically, and spiritually superior to Black people.

Other readers questioned Stowe’s authority to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She was a Northern white woman writing an exposé of slavery, and people from the 19th century until today have questioned whether she had the ability or right to speak for people of African descent. Though Stowe was earnest in her attempts to portray slavery as it really was—gathering an impressive array of facts, figures, and first-person testimonies to supplement her own observations—she would not have had the same insight or understanding as an enslaved person experiencing those conditions. Her reliance on racial stereotypes exposed her misconceptions about Black people, discrediting her authority even more.

Stowe’s position as a white author meant that she had access to larger audiences, and so, even though some doubted her perspective, she was able to reach and influence more people with her powerful argument against slavery.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin opens on the Shelby plantation in Kentucky as two enslaved people, Tom and 4-year old Harry, are sold to pay Shelby family debts. Developing two plot lines, the story focuses on Tom, a strong, religious man living with his wife and three young children, and Eliza, Harry’s mother.

When the novel begins, Eliza’s husband George Harris, unaware of Harry’s danger, has already escaped, planning to later purchase his family’s freedom. To protect her son, Eliza runs away, making a dramatic escape over the frozen Ohio River with Harry in her arms. Eventually the Harris family is reunited and journeys north to Canada.

Tom protects his family by choosing not to run away so the others may stay together. Upon being sold south, he meets Topsy, a young black girl whose mischievous behavior hides her pain; Eva, an angelic, young white girl who is wise beyond her years; charming, elegant but passive St. Clare, Eva’s father; and finally, cruel, violent Simon Legree. Tom’s faith gives him the strength which carries him through years of suffering.

The novel ends when both Tom and Eliza escape slavery: Eliza and her family reach Canada, but Tom’s freedom only comes in death. Simon Legree has Tom whipped to death for refusing to deny his faith or betray the hiding place of two fugitive women.

Read the text of Uncle Tom’s Cabin HERE as originally released in The National Era. You will find each chapter, followed by commentary, and links to Stowe’s A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin and related materials.

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s courage as she picked up her pen inspires us to believe in our own ability to make positive change. Uncle Tom’s Cabin challenges us to confront America’s complicated past and connect it with today’s issues.

Stowe’s vivid characters and portrayal of their struggles opened reader’s eyes to the realities of slavery and the humanity of enslaved people. Stowe hoped the novel would build empathy for the characters and, in turn, for enslaved individuals.

Stowe’s candor on the controversial subject of slavery encouraged others to speak out, further eroding the already precarious relations between northern and southern states and advancing the nation’s march toward Civil War.

By the war’s beginning in 1861, North-South tensions had been on the rise for decades. With the election of President Abraham Lincoln in 1860, the crisis came to a head as some Southern states seceded from the Union. Many white Southerners feared that slavery, “the peculiar institution” upon which their economy depended, would be eradicated. The brutal four-year war that followed almost destroyed the United States.

When Stowe visited President Lincoln at the White House in 1862, he is reported to have said, “So you’re the little woman who wrote the book that started this great war.” This statement, regardless of its truth, testifies to Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s impact.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was a runaway hit, selling 10,000 copies in the United States in its first week and 300,000 in the first year. The novel sold even more copies abroad than it did in the United States — 1.5 million in a year in Great Britain.

When Stowe visited Great Britain in 1853, invited by anti-slavery groups, she was rushed by excited crowds. During her five-month stay, she traveled the country. She attended numerous anti-slavery rallies and was presented with the Stafford House Address, a 26-volume leather bound petition signed by more than 563,000 British women asking their American sisters to work to abolish slavery.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was the first major U.S. novel with a Black main character, and the first to use regional accents. It has been translated to over 70 languages.

Public response to Uncle Tom’s Cabin was not all positive. Moderates praised the book for exposing slavery’s harsh realities, but abolitionists felt it was not forceful enough. Others called out some of Stowe’s characters as stereotypes. Pro-slavery advocates argued that Stowe had written an unrealistic, one-sided image of slavery. These pro-slavery responses prompted at least 29 “Anti-Tom” or proslavery books before the Civil War.

Stowe responded to her critics by writing The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, an annotated bibliography of her sources. In The Key, Stowe pointed out people who inspired her characters and events. She hoped that identifying these sources would demonstrate that her novel was based on fact.

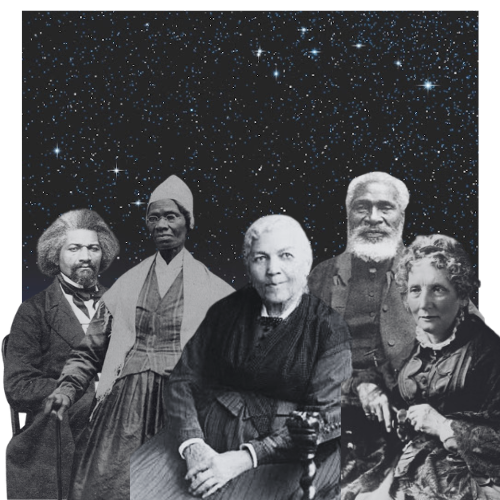

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was part of a large body of anti-slavery writing. Stowe borrowed from books by enslaved people including Josiah Henson, Lewis Clarke, and Solomon Northup. As a white woman, Stowe was seen as less threatening to white readers than Black abolitionists, helping her novel reach more readers. Some thought the book’s success was a tool they could use, while others said Stowe was taking stories that were not hers.

Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s reach went right off the page. It inspired products including wallpaper, board games, silverware, song sheets, ceramics, and handkerchiefs.

It was so popular it immediately became a play, with scenes taken word for word from Stowe’s novel. People flocked to see it and competing New York City shows made going to the theater respectable. Theater companies small and large travelled the country, using their own versions, without anti-slavery messages, and adding spectacle to draw crowds. Because her strict Congregationalist upbringing forbade going to the theater, Stowe was not comfortable collaborating on stage productions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Unfortunately, 1852 copyright laws did not protect fictional works from being adapted into plays without the author’s permission. These products, plays, and spin-offs were created without Stowe’s consent and copied the racial attitudes of their time from 1852 through the Civil War, Jim Crow Era, and as late as the 1950’s.

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin” became the longest running play in U.S. history.

Dramatization of Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s for the stage meant shortening and simplifying a complicated story. These unauthorized productions, known as “Tom Shows,” were loosely based on Stowe’s story. “Tom Shows” were produced in theaters and traveling shows across the country, often with extravagant special effects and comedic dialogue.

Racial stereotypes were highlighted with actors in blackface and simplified plots. Eliza’s escape across the ice added bloodhounds. Topsy became a slapstick figure. Strong, young Tom aged to a submissive, shuffling old man.

Discussions of racism, slavery’s impact on families, and reparations vanished, and after the Civil War, so did most references to slavery. Professional “Tom Shows” toured annually for nearly 90 years, and versions were later filmed for movies and cartoons.

“Tom-Shows” were not the only way others profited from Stowe’s ideas. A wide range of Uncle Tom’s Cabin inspired products, or “Tomitudes,” flooded the market. Some of these items reflect racial attitudes of the day, making uneasy viewing in the 21st century. Although Stowe neither endorsed nor profited from the plays or memorabilia, public perception of her work was altered.

In 2018, writers around the globe selected Uncle Tom’s Cabin as #2 of 100 stories that shaped the world! Read more about it.

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher was born in 1811 in Litchfield, CT. Throughout her life, Harriet would encounter many free and enslaved Black individuals and abolitionist organizations, all of which influenced her to become an anti-slavery author.

Published in 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was the best-selling novel of the 19th century. This novel highlighted the horrors of slavery and called on Antebellum white Christians to take up the cause to end the violent, racist institution.

Later that year, in response to claims that Uncle Tom’s Cabin was not based in fact, Stowe published A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. This 268-page volume collected letters, speeches, and excerpts from Black-authored narratives about the lives of enslaved Black people and their continued fight for freedom.

A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, together with the narratives and collective action of Black freedom builders, would galvanize anti-slavery activism in the 19th-century United States, even influencing major politicians like President Abraham Lincoln.

Slavery ended thanks to the work, words, and courage of a vast constellation of Black abolitionists, literary activists, and storytellers. At the Stowe Center for Literary Activism, we tell the stories of historical figures like Frederick Douglass, Nancy Toney, James Bradley, Harriet Jacobs, Gad Asher, Henry Bibb, Rebecca Primus, Sojourner Truth, Josiah Henson, and many others who advocated for hope and freedom. Their stories moved, educated, and challenged Harriet Beecher Stowe throughout her life, and they continue to hold important lessons for our world today.