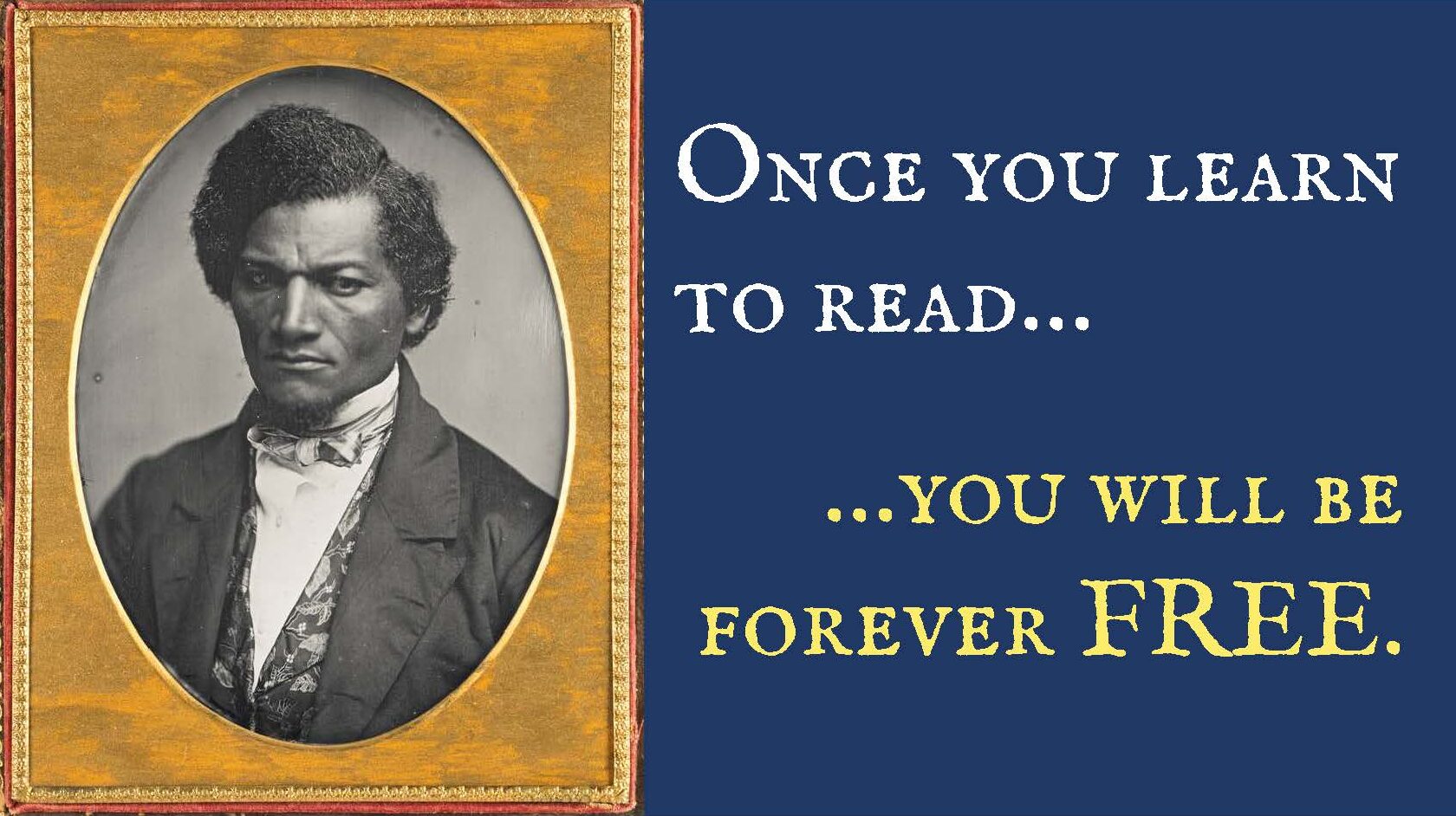

In 2023, the Stowe Center for Literary Activism unveiled a new intergenerational tour called Inheriting Freedom. This tour focuses on the life of Frederick Douglass, whose Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, inspired Harriet Beecher Stowe’s character George Harris, in her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin. We developed this tour as a school tour in the fall of 2024 and have given this tour to hundreds of students and families from across the Hartford area. As part of our program, we have adopted a call-and-response with students using the quote “Once you learn to read, you will forever be free.” When we wrote the script for the tour we had done research on Douglass’s life, scouring books, letters, speeches, articles and biographies written about Frederick Douglass. In so many works, Douglass was attributed as saying this quote, but recently we realized that there was something so much more complex about this quote, what he said, and the impact of literacy on Douglass as an enslaved child and young man. Once you learn to read, you’ll be free but first you will be agitated.

In 1845, Frederick Douglass published his narrative, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. It was a profound account of his life as an enslaved Black man, his journey to literacy, and the struggle to find his freedom. His account was marred with hardship and triumph in different aspects of his life, but one of the major parts of his narrative was the ways in which literacy framed the way he saw and struggled with the world as an enslaved young man. Douglass is attributed as saying “once you learn to read you will be forever free.” While this statement is one that we believe to be true, we must understand that it is a summarization of a longer, deeper reading of Douglass’s words. While it is true that he understood that literacy was “the pathway from slavery to freedom.” (Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, 1845, 33). He also struggled with the complex nature of what being literate in nineteenth century America in the south. Today, we have amplified a paraphrased quote without understanding the full extent and cost of literacy in the nineteenth century. What we discovered in a further reading of Douglass’s work is that he grappled with his understanding that literacy would set him free, but first it would make life harder for him, and not in the ways we might think.

As a child Frederick Douglass was enslaved by the Auld family, at a young age he was sent to the house of Hugh Auld near Baltimore, Maryland. When Frederick came to live with the Aulds, Hugh’s wife, Sophia, began to teach him the alphabet and to spell three and four-letter words. When Hugh found out, he forbid Sophia from teaching Frederick to read, not only because it was illegal but also, as he said because “…Learning would spoil the best [n-word] in the world…if you teach that [n-word] (speaking of Douglass) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave.” (Narrative, 1845, 33). Douglass began to understand that literacy, “…was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.” (Narrative, 1845, 33).

This statement that Douglass makes is fraught with tension, he begins to understand that literacy would be both a gift and a curse for an enslaved Black person in that time. He worked hard to understand not only that he could be free but that he was going to have to fight for his freedom. In his narrative, Douglass specifically speaks about the weight of being literate and being enslaved. Narratives offered some insight into the struggle that Douglass had with literacy, he wrote:

“The reading of these documents [speaking of Sheridan’s speeches for Catholic emancipation in the Colombian Orator] enabled me to utter my thoughts, and to meet the arguments brought forward to sustain slavery; but while they relieved me of one difficulty, they brought on another even more painful than the one of which I was relieved. The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers… that very discontentment which Master Hugh had predicted would follow my learning to read had already come, to torment and sting my soul to unutterable anguish. As I writhed under it, I would at times feel that learning to read had been a curse rather than a blessing. It had given me a view of my wretched condition, without the remedy. It opened my eyes to the horrible pit, but to no ladder upon which to get out… It was this everlasting thinking of my condition that tormented me. There was no getting rid of it. It was pressed upon me by every object within sight or hearing, animate or inanimate. The silver trump of freedom had roused my soul to eternal wakefulness. Freedom now appeared, to disappear no more forever. It was heard in every sound, and seen in every thing. It was ever present to torment me with a sense of my wretched condition. I saw nothing without seeing it, I heard nothing without hearing it, and felt nothing without feeling it. It looked from every star, it smiled in every calm, breathed in every wind, and moved in every storm.” (Narrative, 1845,40-41)

—FREDERICK DOUGLASS

What Douglass describes in his narrative, is what W.E.B. Du Bois coined as the “double consciousness” in his book The Souls of Black Folks (1903), which describes the internal conflict and unique perspective experienced by Black Americans in the United States, stemming from their struggle to reconcile their own cultural identity with the prejudiced views and expectations of the dominant white society.

As we grapple with the abhorrent conditions of slavery and the history of Black literacy, and Black literary activism in this country, we must also understand history of the cost to Black people. Douglass spoke explicitly about the cost to his mental wellbeing. What Douglass spoke about in 1845, was an issue that still plagued Black Americans at the turn of the twentieth century, Du Bois wrote that this dual awareness involves “looking at one’s self through the eyes of others” and can lead “to internal conflict and self-doubt, but also offers a unique insight into society and a basis for activism and cultural resilience.” It is important as learners of history to understand the full breadth of the words of historical figures. To summarize history sometimes means that we lose the nuance of that story. In Douglass’s case, he knew that literacy was going to be the thing that freed him and all Black people from the bonds of slavery, but what he experienced was a sort of cognitive dissonance. He knew what life was, and that was hard, but he also knew that reading, writing and orating could make life better for so many.

In 1849, transcendentalist and Unitarian minister, Theodore Parker in his speech, “The Position and Duties of the American Scholar” stated “all the original romance of Americans is in [the slave narratives], not in the white man’s novel.” By March 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe, inspired by the narratives Black freedom seekers, abolitionists and activists, had published her book Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or Life Among the Lowly. And when southern whites, and proslavery advocates denounced her book as unjustified lies, Stowe produced a work unlike any other of its time The (A) Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a book filled with excerpts from Black narratives, letters written by Black Americans about their struggles, and anecdotes of encounters she had with Black women who worked in houses that she resided in. It is the legacy of Black literary activists, who sought freedom not only for themselves but for generations of Black Americans, that has enabled the legacy of Harriet Beecher Stowe. At the Stowe Center for Literary Activism, we honor that legacy. We are honored to have The Key as a roadmap and wayfinding tool to amplify Black voices.